By Eamonn Ives (Research Director, The Entrepreneurs Network) and Derin Kocer (Adviser, The Entrepreneurs Network)

Executive summary

Of the United Kingdom’s 100 fastest-growing companies, 39 have a foreign-born founder or co-founder;

These immigrant founders come from across the world – with America being the most common origin country, followed by Germany and India;

Compared to our previous analysis last year, the proportion of Britain’s fastest-growing companies with a foreign-born founder or co-founder has remained constant – but it is still down from 49 of the top 100 since 2019;

We believe this shows the critical contribution that international talent makes to Britain – without their effort and vision, our economy would be less dynamic and competitive;

It also underlines the importance of having an immigration system which enables high-skilled individuals and those with high potential to come to Britain;

We conclude with a series of policy recommendations to improve Britain’s immigration system, to ensure the world’s brightest and best can continue to contribute to our economy:

Reform eligibility thresholds to help startups and high-growth businesses access talent;

Harness the Immigration Salary List to buttress the Government’s industrial priorities;

Negotiate Youth Mobility Schemes with the European Union and the United States;

Lower visa fees for high-skilled immigrants in line with international competitors;

Expand the High Potential Individual visa to more universities;

Build a specialised task force to recruit international talent;

Grant advanced STEM students Indefinite Leave to Remain upon graduation;

Introduce the world’s first Global Talent Exam to actively recruit the world’s brightest individuals.

foreword

Fragomen supports The Entrepreneurs Network and Beauhurst to deliver the latest data reflecting the significance of migration and mobility to the UK’s entrepreneurial landscape. This analysis will help inform the evidence-based case for policies and an immigration architecture that distinctly encourages, supports and nurtures entrepreneur-arrivals. As the analysis highlights, foreign-born startup founders have been and are integral to the success of the UK’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. Reforms can ensure the UK continues to attract the world’s brightest minds who will collaborate alongside homegrown innovators for continued and dynamic economic growth.

Furthermore, with economic growth being a central mission of the new Government, the policy ideas suggested by The Entrepreneurs Network to enhance the UK’s attractiveness to entrepreneurial talent are welcome focus points for potential reforms.

Dynamic reform is essential in today’s rapidly evolving global market, where the UK must innovate and compete not only with other nations but also for the best available talent. With global talent in short supply and fierce competition exacerbated by demographic challenges like aging populations and increased inactivity, as well as technological advances reshaping the expertise needed, the urgency for action is clear. Projections suggest a global talent shortage of 85 million by 2030, with 75% of countries aging by 2050 and 44% of core skills changing within the next five years. As competitor markets implement migration policies to boost economic productivity, particularly in sectors facing intense competition for talent, the UK must act swiftly to remain a key player in the global economy.

Fragomen supports reforms creating environments in which entrepreneurial innovation can flourish. As the global landscape evolves, it is crucial that government, industry, and advocacy groups work together to craft policies that not only address current needs but also anticipate future demands. This strategic collaboration cultivates a resilient and inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem, ensuring long-term prosperity and success for the UK’s economy and society.

Nadine Goldfoot – Managing Partner, Fragomen

Introduction

Talent is critical to the growth and competitiveness of all businesses in the modern global economy. The skills, knowledge, and entrepreneurial drive of a workforce directly impact productivity, innovation and overall economic performance. As nations increasingly compete on the basis of human capital rather than physical resources, understanding how to boost talent levels has become a central concern for policymakers and business leaders alike.

One of the easiest and fastest ways to increase an economy’s skills base is through immigration. Not only do immigrants increase talent in an absolute sense by adding their own skills into the mix, they also deepen labour markets, which theory dictates allows for greater division of labour and specialisation. Their skills complement existing skills or free up other workers to be employed in more productive roles, empowering everyone to do what they do best.

Immigrants’ contribution to economic growth is corroborated by data from multiple countries. Enterprise data from the United Kingdom and France show that businesses with more immigrants are more likely to innovate and experience higher productivity. Similarly, immigration has positively influenced overall productivity growth in the United States for decades – it’s estimated that approximately one third to a half of the increase in productivity growth since the 1960s could be attributed to enhanced specialisation and efficiency thanks to immigrants.

Our Job Creators research series – and Immigrant Founders project at large – has also been gathering evidence that demonstrates migrants’ entrepreneurial contribution for the past several years. In 2019, we found that almost half of Britain’s 100 fastest-growing companies had an immigrant founder despite foreign-born individuals making up less than 15% of the UK’s population. Last year, we found that the ratio decreased to 39 out of the Top 100 – due, we argued, to the twin impacts of Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic. This year, we can reveal that the figure has stayed constant at 39 out of the Top 100. What all of our research has found is that immigrants play a disproportionate part when it comes to starting some of the most dynamic, promising and influential companies in the British economy, and that those same companies are often heavily reliant on sourcing the globally scarce skills they require from abroad when they cannot find them at home.

Yet despite the positive story we have been able to tell, the recent public debate around immigration has been altogether more negative. Before the last Conservative Government was voted out of office, it used high immigration numbers to justify policies and language that have damaged Britain’s attractiveness for future high-potential migrants.

A combination of new salary thresholds, restrictions on dependants and a re-emergence of hostile rhetoric is already causing problems for top British universities looking to entice international students. Relatedly, multiple large companies have withdrawn job offers to foreign graduates because of the new migration rules. Anecdotally from our own conversations with startup founders and investors, the sense that Britain has become a less attractive place in which to grow a business because of its shift in immigration policy of late has been palpable.

Immigration’s return to prominence as an issue of concern belies the fact that the British public has very nuanced views on it. Surveys consistently show that high-skilled immigrants are welcomed by the majority of the British electorate. So too is there support for Ukrainians and Hongkongers who came to Britain for humanitarian reasons, and drove a considerable portion of the recent rise in immigration. We contend that it is eminently possible, and indeed desirable, to craft an immigration system which enables the sort of immigration people are comfortable with, while still retaining control of our borders.

Advanced economies are on the lookout for international talent like never before. This has long been the case, but technological advancements and looming demographic challenges now make it critical. As geopolitical headwinds and the advancement of revolutionary technologies like AI create instability and uncertainty, securing the future within allied countries will also be of utmost importance. The UK cannot afford to sit idly by – its population of immigrants contribute enormously to the country’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, and despite recent changes, it remains a destination where many talented individuals want to build a future for themselves and others. It is the job of the new Government to craft a policy environment that ensures that can continue long into the future.

Key findings

While less than 15% the UK population is foreign-born, 39% of the UK’s 100 fastest-growing companies had a foreign-born founder.

Our latest analysis reveals that while less than 15% of the British population is foreign-born, 39 of the UK’s 100 fastest-growing companies have a foreign-born founder or co-founder. This is the exact same proportion as we found last year, but a drop from 49 of the ‘Top 100’ when we first analysed the data in 2019.

Among the 208 founders and co-founders behind this year’s companies, 66 – or 32% – were born overseas. These statistics underscore the significant contribution that immigrants make to the UK’s entrepreneurial landscape. Within the Top 100, 13% of the companies were established entirely by foreign-born teams, while 26% were joint ventures between British and immigrant co-founders.

Infographic 1. Immigrants play a disproportionate role in the creation of the United Kingdom's fastest-growing companies

The disparity between the proportion of foreign-born founders in the Top 100 and the foreign-born population in the UK at large is striking. These numbers undeniably reveal that immigrant founders constitute an outsized proportion of the most dynamic and rapidly growing companies. Without their contribution, Britain’s economy would have fewer jobs, the Treasury less revenue, and society would be denied direct access to a swathe of innovative and beneficial goods and services.

Infographic 2. Immigrant founders of Britain's fastest-growing companies come from all over the globe

Comparing this year’s Job Creators data to those in our 2023 iteration, we observe slight changes in the nationalities of migrant founders. Last year, the founders hailed from 28 different countries, whereas this year it has fallen to 22. The US remains the largest contributor of foreign talent (which was also true in 2019, the year we started our Job Creators series). India, Canada, Australia, France and Germany continue to be significant sources of entrepreneurial talent too, while Lithuania and Poland feature for the first time.

Unsurprisingly, most of these migrant-founded companies are based in cities and towns with large migrant populations. Out of the 39 fastest-growing companies with foreign-born founders, 31 are located in London, which is followed by Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Bristol.

The industries represented by these companies are diverse, with a significant emphasis on technology. Software and technology companies are the most prevalent – making up more than half of the Top 100 – followed by consumer goods firms, finance and banking services, energy startups, and manufacturing enterprises. Most of these firms are focused on innovating in critical industries, including sustainable energy and healthcare.

Overall, these numbers show that even though hostile rhetoric on immigration has increased in recent times, foreign-born individuals continue to play an outsized role in starting and growing innovative companies which advance the UK’s economy. This finding underscores the importance of fostering an environment that welcomes and supports high-skilled immigrants, many of whom work at the cutting edge of science and technology, ensuring that the UK remains a hub for innovation and growth.

However, what these numbers don’t capture is the impact of the previous Government’s migration policies, which in a recent statement to the House of Commons the new Home Secretary Yvette Cooper broadly pledged her ongoing support for – not least the increase in salary thresholds to obtain Skilled Worker visas. If maintained, these reforms will likely continue to deter many potential entrepreneurs from coming to the UK, as well as incentivising gifted foreign students to leave the country upon graduation. With our new data once again reaffirming the contribution immigrants make to Britain’s startup landscape, we encourage the new Government to think carefully about what can be done to improve the immigration system to attract more of the world’s brightest and best.

case study: Mission Zero Technologies

“If you’re coming into a country from outside, you’re going to see some things differently” — Shiladitya Ghosh – COO and Co-Founder, Mission Zero Technologies

Formed in 2020 by three scientists who were increasingly alarmed at the threat of global warming, Mission Zero Technologies aims to tackle the climate crisis head on. By harnessing a groundbreaking process pioneered by one of their co-founders, they use water, a catalyst and renewable electricity to directly take carbon out of the atmosphere. Their solution has the potential to operate almost anywhere in the world and they hope to scale it to the point where they are removing gigatonnes of carbon from the air each year. Since starting up they’ve won funding from the British government and agreed a contract for carbon removals from Stripe.

Mission Zero Technologies has three co-founders – Nick and Gaël, each born in the United Kingdom, and Shiladitya, born in Canada to Indian parents and raised in Singapore. Shiladitya came to the UK in 2012 to study at Imperial College – first completing a Master’s there and then receiving his PhD. Britain’s academic reputation, especially for STEM, and the close partnerships between universities and the private sector were all key factors which made moving to the UK so appealing for him.

Setting up Mission Zero Technologies in the UK was an obvious first choice for Shiladitya and his co-founders. For a start, it was where they were all based when they met. Second, the UK has inherent natural advantages for renewable power that make it a good place for deploying climate technology. Shiladitya also describes how at the time they launched the government had a good policy framework in place for both scaling early stage climate tech and planning large scale carbon capture and removal hubs, and they also believed that they could become the national champion for their industry, to challenge competitors in the US and Europe.

As well as having a mixed-nationality founding team, the wider team at Mission Zero Technologies is similarly diverse. Shiladitya says of the roughly 40 employees they have, there are 14 different nationalities, and notes how this is an asset to the business: “We’re spoilt with great minds to work with.” He also believes that the risk appetite of immigrants is typically higher, and thinks this is crucial to having a go and trying something new: “If you’re coming into a country from outside, you’re going to see some things differently.”

While Shiladitya thinks that Mission Zero Technologies has had a reasonably easy journey with respect to hiring non-British staff, he’s well aware of other companies that have struggled with the bureaucracy, delays and expense involved with the visa system – especially for startups at the earliest stage or without as much funding. Shiladitya also wonders whether some foreign talent may be looking at the UK less favourably now, and instead thinking about moving to other countries whose immigration systems are more easily navigable. As he puts it: “The types of available work visas have changed multiple times since I’ve lived in Britain, which makes it more complicated for entrepreneurs to plan to either move to, or stay in, the UK. This is in stark comparison to the US, where innovators have known their options for a long time. Having more certainty over visa routes would be a simple yet critical step to attract more top talent.”

case study: ENODA

“We talk all the time about moonshots, but you’d never take one on a cost-benefit analysis” — Paul Domjan – Chief Policy and Global Affairs Officer and Co-Founder, ENODA

ENODA is solving the most complex challenges at the heart of the energy transition, to deliver the core, electricity grid technology that will enable decarbonised, reliable and affordable energy. Established in 2021 and headquartered in Edinburgh, ENODA was formed by a group of four founders, three of whom hail from overseas.

One of those founders is Paul Domjan. Originally from Texas, USA, Paul first moved to the United Kingdom in 2001 as a Marshall Scholar to study for a Master’s at the University of Oxford. He speaks glowingly of the UK’s higher education system, describing it as “the jewel in Britain’s crown, and an asset for attracting skilled people into the economy.”

Indeed, Paul notes that one of the key reasons ENODA is based where it is, is because of the proximity to the universities, other world-class engineering firms, and the talent pool that Edinburgh offers.

Of the roughly 100 people ENODA now employs, around half were not born in the UK. Paul believes that foreign-born talent has been vital to ENODA’s success: “Some of the people we’ve hired are the only people in the world who can do what they do,” he explains. “It’s not just about the technical skills either, as immigrants will also provide different perspectives when it comes to tackling challenges. This helps everyone to be as productive as possible.” Altogether, the company counts 23 different nationalities in its workforce.

Paul also highlights how critical immigration is to the wider entrepreneurial ecosystem. He notes that foreign-born founders bring with them connections and capital that wouldn’t otherwise be on offer for the host country. This has been important for the UK in the past, and Paul thinks it will be essential if the new Government is to confront Britain’s “number one challenge,” as he sees it, of changing how business growth is thought about in the UK. He believes that while the UK is great at starting businesses, more needs to be done to encourage founders to grow them over longer periods and to greater scale. He contrasts this with his native US, where starting up a business only to sell it once it has started to do well would be seen as a failure.

With respect to the current state of the debate around immigration, Paul expresses concern about recent changes which could make it harder for overseas talent to secure visas, or which might deter skilled foreigners from trying their hand at entrepreneurship. He argues that too many people think about immigration ‘transactionally’. As he puts it: “We talk all the time about moonshots, but you’d never take one on a cost-benefit analysis.”

Policy Proposals

Countries across the globe are racing to attract talent to their shores. The US has been actively reforming its exceptional talent visa pathways to open them up to specialised talent, especially AI engineers. Canada has been piggybacking on the American immigration system to offer easier visa schemes to high-skilled foreign workers. Germany is starting to offer ‘Opportunity Cards’ to skilled foreigners to move to the country without job offers. China, on the other hand, has been investing heavily in policy schemes to re-attract its talented youth who have been educated in the Western world.

It would be unfair to say previous British governments have been completely blind to these developments. On the contrary, policies like the High Potential Individual visa – which gives a two-year-long visa to recent graduates of the world’s top universities – is one of the most creative schemes in the developed world.

Overall, however, political concerns regarding migration figures have left British politicians hesitant to reform high-skilled immigration along with the actual requirements of the country and international trends. The increase in salary thresholds to obtain a Skilled Worker visa, considerations to scrap the Graduate Route, and the failure to distinguish skilled migration and illegal immigration has plunged individuals and businesses into policy uncertainty.

It’s time for the new Labour Government to be bold and pro-actively reframe this debate by putting the race for top talent at its core. The historic migration figures, accelerated by exceptional international events like the invasion of Ukraine and China’s policies toward Hong Kong, are already coming down. Thanks to its culture, history, economic opportunities and broadly welcoming population, the UK is naturally attractive for skilled immigrants. While challenges still remain, Britain does far better than many other European countries in terms of integrating migrants and offering them and their children opportunities to build a future here. We should lean into our strengths, understand high-skilled immigration as a British superpower and adopt a reforming agenda to welcome more of the world’s top talent to our towns and cities.

Below are eight broad reforms that can be implemented by the Government that would make a huge difference.

1. Reform eligibility thresholds to help startups and high-growth businesses access talent

The new immigration rules, introduced by the former Conservative Government last year, increased the minimum salary threshold for skilled workers coming into the country from £26,200 to £38,700 – which is £4,000 higher than the average salary in the UK. This threshold varies depending on professions and roles. Previously, the thresholds were set at the 25th percentile for Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) data, but with the new changes these rates have now been increased to the 50th percentile. This means that companies hiring software engineers are required to pay them a minimum salary of £49,400 if they want to employ a foreign worker.

The new salary threshold may not be an insurmountable hurdle for experienced professionals working for bigger companies, but it will be much harder for startups to pay these salaries and for foreign students of the UK’s leading universities to surpass these thresholds upon graduation. Young people will increasingly find they will need to work for established corporations instead of innovative challengers.

Additionally, the new thresholds are making life even more difficult for academic researchers, most of which are foreign-born. Although they are leading innovation, most of the work they do is not commercial. This can translate into low salaries but that doesn’t render their work less valuable. For instance, at the University of Oxford the starting salary for a postdoctoral researcher stands at around £36,000 – below the minimum earnings threshold. The Government should also consider that the new thresholds will exacerbate regional imbalances as companies outside the Oxford-London-Cambridge triangle typically pay even lower salaries.

The new Government should immediately reform the new rules to make them work for Britain’s leading startup ecosystem and distinguished academic institutions. It can do this first by extending the length of time employees can be eligible for ‘New Entrant Rules’ – which lower the salary threshold for younger employees – when on a Skilled Worker visa.

Currently, ‘new entrants’, who are usually in the early stages of their career, can be paid a reduced salary for a maximum of four years if they meet certain defined criteria. But this includes any time spent on the Graduate visa, and so may not cover the entire period (three or five years) for which a Skilled Worker visa can be secured. This means individuals may be exposed to unattainable jumps in salary requirements after a relatively short time on a Skilled Worker visa, and certainly before they reach the point (after five years) of being eligible to apply for Indefinite Leave to Remain under that route. The period an employee can benefit from New Entrant Rules should therefore be modified and prolonged – to exclude any period spent on the Graduate route, and to be increased to five years under the Skilled Worker route

Second, equity ownership should count towards the salary thresholds. For quickly growing firms, which may lack meaningful cash flow, giving ownership in the company is a common way to attract talent which also increases the chance of sustainable firm growth. The UK’s immigration framework must factor this in so that startups can compete for talent against the giants.

Lastly, given their importance to growth and innovation and their unique role in the economy, academic research institutions should be kept outside the new salary thresholds. The government should work with universities and other academic organisations to define which institutions this includes. The cost of scientific progress should not be artificially driven up by a visa system that is inflexible to reality.

2. Harness the Immigration Salary List to buttress the Government’s industrial priorities

Earlier this year, the Immigration Salary List replaced the Shortage Occupation list, with job categories featuring on it being subject to a lower general salary threshold and a marginally lower visa application fee. The motivation behind the change was to “make clearer that the entries on the list are those where the Government considers it sensible to offer a discounted salary threshold, rather than being a list of all occupations experiencing labour shortages.”

In theory, there is much to commend with the idea of offering some flexibility in salary thresholds for certain occupations. It recognises that a fixed, arbitrary salary threshold is not necessarily the best way to craft an immigration policy which enables skills the economy demands to easily come into the country. But there is still further to go.

The new Government should harness the Immigration Salary List so that it works to actively buttress the UK’s industrial priorities and strengths. For instance, Britain’s leadership in technology and financial services is evidently an advantage we hold over much of the rest of Europe. Additionally, Labour’s objective to lead on green energy is also clearly a national priority – one that requires considerable investment in new infrastructure.

However, the cost of these investments would be needlessly inflated if businesses cannot also access the talent that they need. As seen in the US, although government subsidies have helped get semiconductor projects started, even the giants of the industry had to stall the construction of new fabs due to talent shortages. The new Government should see immigration as an essential part of industrial policy and use the Immigration Salary List as a lever to help achieve its goals.

3. Negotiate Youth Mobility Schemes with the European Union and the United States

Forging a closer relationship with the European Union is a stated priority of the new Government, and a clear and obvious way to do this is to negotiate a Youth Mobility Scheme (YMS) with the European Union. Britain already has YMSs – which allow those aged between 18-30 years old (or 18-35, depending on the country) to easily come and work in the UK for up to two years – with Australia, New Zealand, Canada, San Marino, Monaco and Iceland. Applicants from Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan can also use the scheme if they are selected in a ballot.

Ever since the UK left the EU, it has raised barriers to young Europeans wanting to move to Britain. This has made it harder for a relatively well-educated and skilled population with a broadly common set of values, culture and interests to contribute to our economy and forge ties with the UK. By expanding a YMS to the EU, or by negotiating a similar treaty designed for European countries which can count towards an individual’s Indefinite Leave to Remain, the UK can quickly expand its talent pool and fill skills shortages in numerous industries.

We should also recognise the role that American immigrants play in our startup ecosystem, and seek to negotiate a YMS with the US. Consistently, individuals from the US have established the plurality of Britain’s Top 100 fastest-growing companies that have a foreign-born founder. It is likely that number would increase if we had easier pathways for Americans to come to the UK. With political question marks hanging over the future of the US, a YMS could enable aspirational Americans to relocate to the UK and deploy their talents here.

4. Lower visa fees for high-skilled immigrants in line with international competitors

Ask any immigrant you can find and almost all would agree that Britain’s visa fees are unbearably expensive compared to other countries’. The facts support the sentiment – according to the Royal Society’s estimates, based on data provided by Fragomen, visa costs have increased by over 129% since 2019. Total upfront costs for obtaining a visa from the UK are more costly than other peer countries. It costs nearly seven times as much for a skilled worker to come to the UK for five years with their spouse and a dependent compared to Australia, over 12 times as much compared to Canada and over 86 times as much compared to Germany.

Infographic 3. The United Kingdom's visa fees are uncompetitive compared to other nations

Source: Authors’ analysis of the costs associated with the UK’s Skilled Worker visa, Australia’s Skilled Employer Sponsored visa, Canada’s Federal Skilled Worker visa and Germany’s Work visa for qualified professionals.

Although the UK is a popular destination in spite of these costs, we are not at the top of the list for future migrants and most of our peer countries are both more popular and their immigration systems are less costly. This does not mean that Britain should lower the fees to Germany or Canada’s levels at one stroke, especially not when the public finances are in such a difficult position. However, the past decade’s trend to increase them should be reversed by the new Government.

To do so, the Government should recognise the wrong incentives and structures in place for the decision-making on visa fees. Right now, the Home Office is using the revenue from visa fees to fund itself. For that reason, it’s unlikely that it will commit to lowering these fees. It requires political leadership and endurance, with the Treasury taking on the upfront costs for the long-term gain.

To then actively start to reduce migration costs, the Government should reform the Immigration Health Surcharge (IHS) which in February 2024 was increased by 66%, from £624 to £1,035 per year. Migrants pay this fee to cover their potential use of the NHS. However, immigrants who work in the UK, also pay National Insurance Contributions, like the rest of the population. This is basically therefore a double tax on high-skilled migrants.

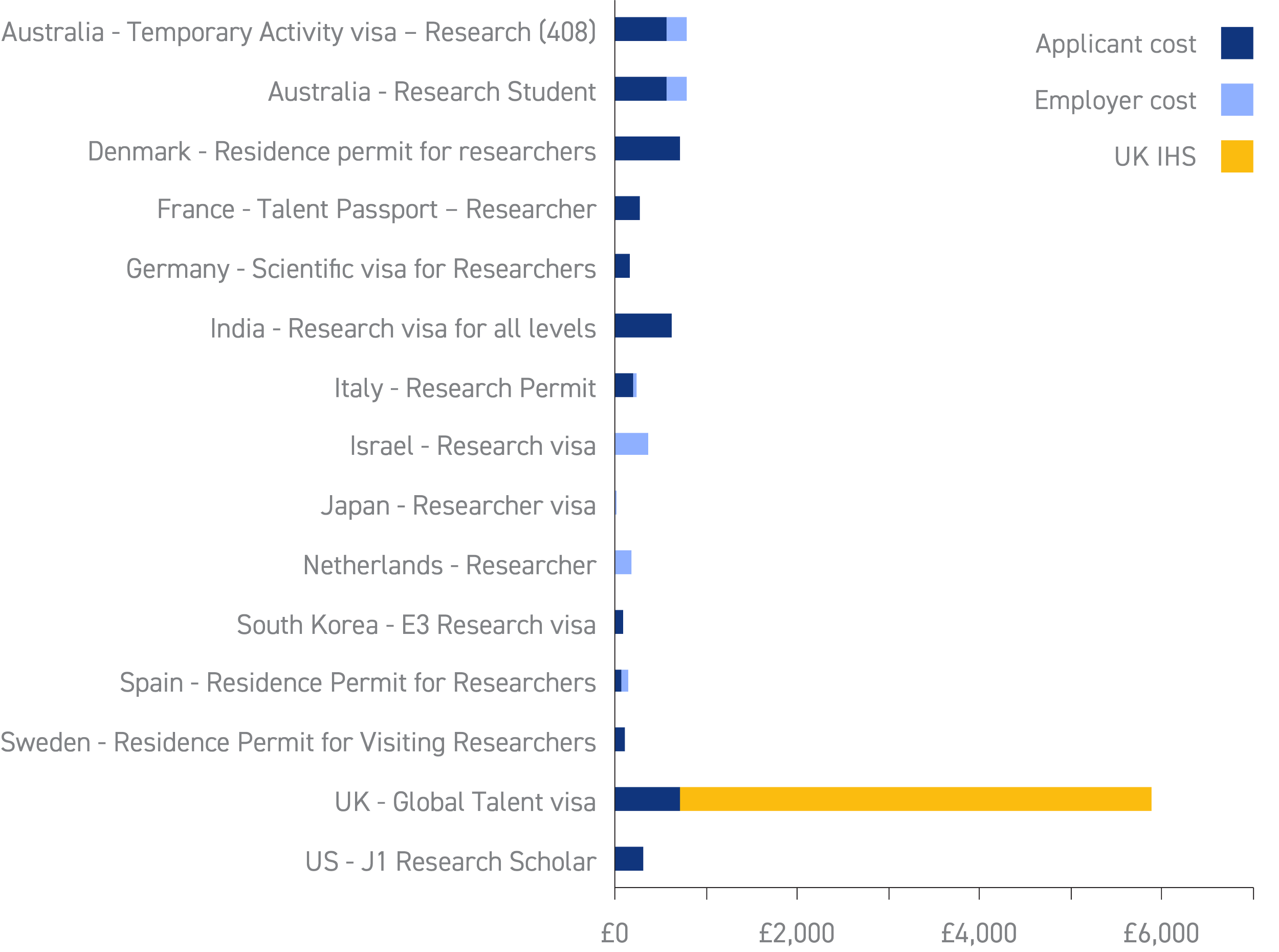

Infographic 4. UK Global Talent visas are much more expensive than similar visa routes for researchers in other leading science nations

Source: Adapted from The Royal Society (2024). Summary of visa costs analysis.

Firstly, the Government should look to scrap this for skilled workers while maintaining it for dependants. Secondly, it should also turn the IHS into an annual tax rather than an upfront payment. To a recent graduate with an entry-level salary, paying for a five-year IHS could cost more than a month’s salary. Finally, the Government should scrap the IHS as soon as possible for migrants that it deems as extraordinarily talented – researchers and scientists with Global Talent visas, for example. Peer countries offer this group of people seamless migration processes while we impose a Talent Tax on them.

5. Expand the High Potential Individual visa to more universities

The High Potential Individual (HPI) visa is one of the few genuinely good immigration policies the previous Government implemented. This migration route allows graduates of top foreign universities to come to the UK for at least two years, giving them the right to look for jobs and other opportunities. In a way, it piggybacks off the work other countries’ top academic institutions put in to identify and attract talent.

Although the HPI visa is innovative, its static eligibility criteria are limiting its potential. Currently, universities must be in the top 50 of selected international ranking lists to qualify. However, due to the methodologies used in these rankings, many specialised institutions, including leading business schools, are excluded. In fact, as we found in our report True Potential, the majority of the top 25 universities measured by average earnings upon graduation are not eligible. Only 42 universities qualified for the HPI visa this year, none of which were specialised institutions and only nine were non-Western.

Increasing the diversity of eligible universities would also recognise the growing quality of higher education outside the Western world. Over the past decade, the number of top-performing universities from developing countries has steadily increased. Graduates from top Indian universities, for example, are now leading global companies like Alphabet, IBM and Microsoft.

To enhance the effectiveness of the HPI visa, the eligibility criteria should first be expanded to include 100 universities. This change could be enacted immediately, and would broaden the reach of this visa, attracting more top talent to the UK. It would facilitate access to skilled individuals for British businesses and research institutions, draw talent to the thriving startup ecosystem, and boost the UK’s entrepreneurial potential.

But for more comprehensive reform, we should actively look at how the eligibility criteria are designed. We have previously suggested ways for graduate earnings data to be factored into the HPI visa. Reforms along these lines would doubtlessly be more complicated, but by no means excessively, and the prize on offer is a HPI visa that can truly select for the world’s most productive graduates.

Uptake of the HPI visa can also be increased by promoting the reformed pathway, particularly in newly included universities. This promotion campaign should be conducted through the long-standing GREAT campaign and British embassies and High Commissions.

6. Build a specialised task force to recruit international talent

Britain’s strategy for attracting talent is generally a ‘passive’ one, but the new Government should adopt a much more proactive approach to enabling international talent to come to the UK. Although this goes against the conventional grain of formulating migration policy, which builds pathways for people to come rather than inviting them to do so, it has historical precedence.

After the Second World War, the US initiated Operation Paperclip to actively recruit around 2,000 German engineers and scientists. They became leading figures in American academia, helping to pioneer flagship initiatives like the US space programme.

The UK should look to emulate this unusual policy to approach leading researchers and entrepreneurial talent. This task force could be part of the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA), which is independently picking and funding high-risk, high-reward research projects. Their existing know-how and networks would make them a common sense home for searching for international talent. They can then reference the applicants’ Global Talent visa applications, streamlining the migration process.

7. Grant advanced STEM students Indefinite Leave to Remain upon graduation

Attracting and recruiting talent goes a long way – but retaining the talent Britain already has can also make a huge difference in the short term. Right now, the overwhelming majority of international students of top UK universities leave the country rather than join the workforce. This is talent that the UK has helped to nurture, but cannot directly benefit from if it departs.

The UK should act boldly to create better incentives for the most promising students. For instance, students who work at the cutting-edge of science and engineering should get a smooth path to stay and build a life in the UK.

To match the competition, the UK should consider granting doctoral students who are pursuing advanced STEM degrees Indefinite Leave to Remain upon graduation. This would incentivise top talent to come and do research in the UK, and give them the freedom to pursue their own projects after studying.

8. Introduce the world’s first Global Talent Exam to actively recruit the world’s brightest individuals

Talent is everywhere but opportunities are not. Conventional visa schemes look for track records of conventional measures of success. Although this works for the overwhelming majority of cases, they do not necessarily give people with extraordinary or unusual talents the same chances. For that to happen, the state needs to act as a ‘recruiter’ rather than a mere process manager – something no country is currently doing.

To lead the way, Britain should trial ‘Global Talent Exams’. These should be open to anyone worldwide with the necessary language skills. Exams would assess applicants’ fundamental abilities like problem-solving, cognitive skills, and analytical thinking. High achievers on these exams would then be interviewed by designated ‘talent searchers,’ who would make the final decision on the candidates’ outcomes. This proactive approach would help identify and nurture talent, providing opportunities for them to succeed.

The UK could then accept a limited number of candidates each year and assist them in settling into their new surroundings, helping with housing, networking and accessing finance. An example of how this could work is the British entrepreneurial organisation Entrepreneur First. Instead of investing directly in startups, Entrepreneur First selects talented individuals with entrepreneurial potential to join their network. These individuals find co-founders and leverage the network to build their businesses. A similar international programme could create unique talent pools, with investors, venture capitalists and governments collaborating to support projects that will eventually flourish.

The Government would then continuously monitor the success of applicants and evaluate the best ways to pick them. Given the boldness of the idea, this programme would initially need to be open to continual evolution until it finds its best working methodology.

Conclusion

Extraordinary people are what drive economies forward. The modern world was built, as we’ve noted before, thanks to “the incremental and accumulated work of just a few thousand innovators.” Accessing the right talent is therefore key to ensuring Britain plays a leading part in continuing to build the future.

Domestic talent will always be the foundation of our economy’s success. However, in the modern age, where specialised knowledge and skills are essential for further progress, so too is extending the talent pool to the best and brightest of the world. Immigrants’ contributions will be invaluable for adding to and complementing the existing skills base of Britain’s workforce.

It’s not only a matter of economic potential – it’s also a matter of strategic importance. Many bright, foreign minds were responsible for the Manhattan Project and Project Apollo. It’s not a coincidence that countries across the globe are looking for ways to attract and retain talent to get ahead in emerging industries like AI and healthtech.

The new Labour Government should not repeat the mistakes overseen by the Conservatives in recent years by fixating on overall migration numbers. Rather, we should build a migration framework aligned with our core strategic interests – be it leading innovation in green energy or novel technologies – and enhance immigration routes for the world’s top talent.

Compared to many other countries, Britain does a better job when it comes to integrating newcomers into society. It’s perhaps therefore not surprising that so many of them are able, as our research reveals, to play an outsized role in launching the sorts of fast-growing and dynamic businesses that enhance our productivity and spur innovation throughout the economy.

High-skilled immigration is an economic asset, not a hindrance – and it’s time to recognise and embrace that fact.

Partner – Fragomen

We are extremely grateful to Fragomen for generously partnering with us on this research project. Fragomen is a leading firm dedicated to immigration services worldwide. T he firm has nearly 6,000 immigration professionals and support staff in more than 60 offices across the Americas, EMEA and Asia Pacific and offers immigration support in more than 170 countries.

The firm supports all aspects of global immigration for corporate, academic, nonprofit, and individual clients, including strategic planning, quality management, reporting, case management and processing, compliance program counseling, representation in government investigations, government relations, complex matter solutions, and litigation. Fragomen is a long-time leader in the immigration technology space and continues to lead the way in the digitization of the immigration journey. Fragomen Technologies Inc., a Fragomen subsidiary, focuses on the nexus of law and technology to further enhance the firm’s productivity, efficiency, innovation and overall technology offering.

These capabilities allow Fragomen to work in partnership with individuals and corporate clients across all industries to plan talent strategy, facilitate the transfer of employees worldwide, and navigate complex challenges.

Methodology

This research uses data from Beauhurst. With their data, we established a list of the 100 companies which had experienced the greatest growth in reaching a valuation observed between June 2023 and May 2024. The list excludes companies that had raised in total less than £25,000, had a pre-money valuation of less than £1 million at the end of 2021, or that gave away a majority stake in their pre-January 2022 equity transaction.

From this list, we established who the founders of those companies were, and their respective nationalities. We cross referenced this with further research and analysis of Companies House data, and finally reached out directly to the companies to verify the information was accurate.

While we recognise that any metric designed to identify the UK’s fastest-growing companies will have drawbacks, we nonetheless believe the Top 100 is a useful snapshot of the UK’s most innovative and high-growth startups and scaleups.

For more information about Beauhurst, please contact Henry Whorwood, Head of Research & Consultancy at henry.whorwood@beauhurst.com.

Beauhurst is the ultimate private company data platform. Beauhurst sources, collates and analyses data from thousands of locations to create the ultimate private UK company database. Whether you’re interested in early-stage startups or established companies, Beauhurst has you covered. Beauhurst's platform is trusted by thousands of business professionals to help them find, research and monitor the UK’s business landscape. For more information and a free demonstration, visit beauhurst.com.

For the full version of the report, which includes footnotes to the evidence cited, click here.