This article is sponsored content from The Economist. To enjoy more of the same, subscribe to The Economist, 12 weeks for £12.

The evidence is mixed; it seems clear, however, that they are making us unhappier

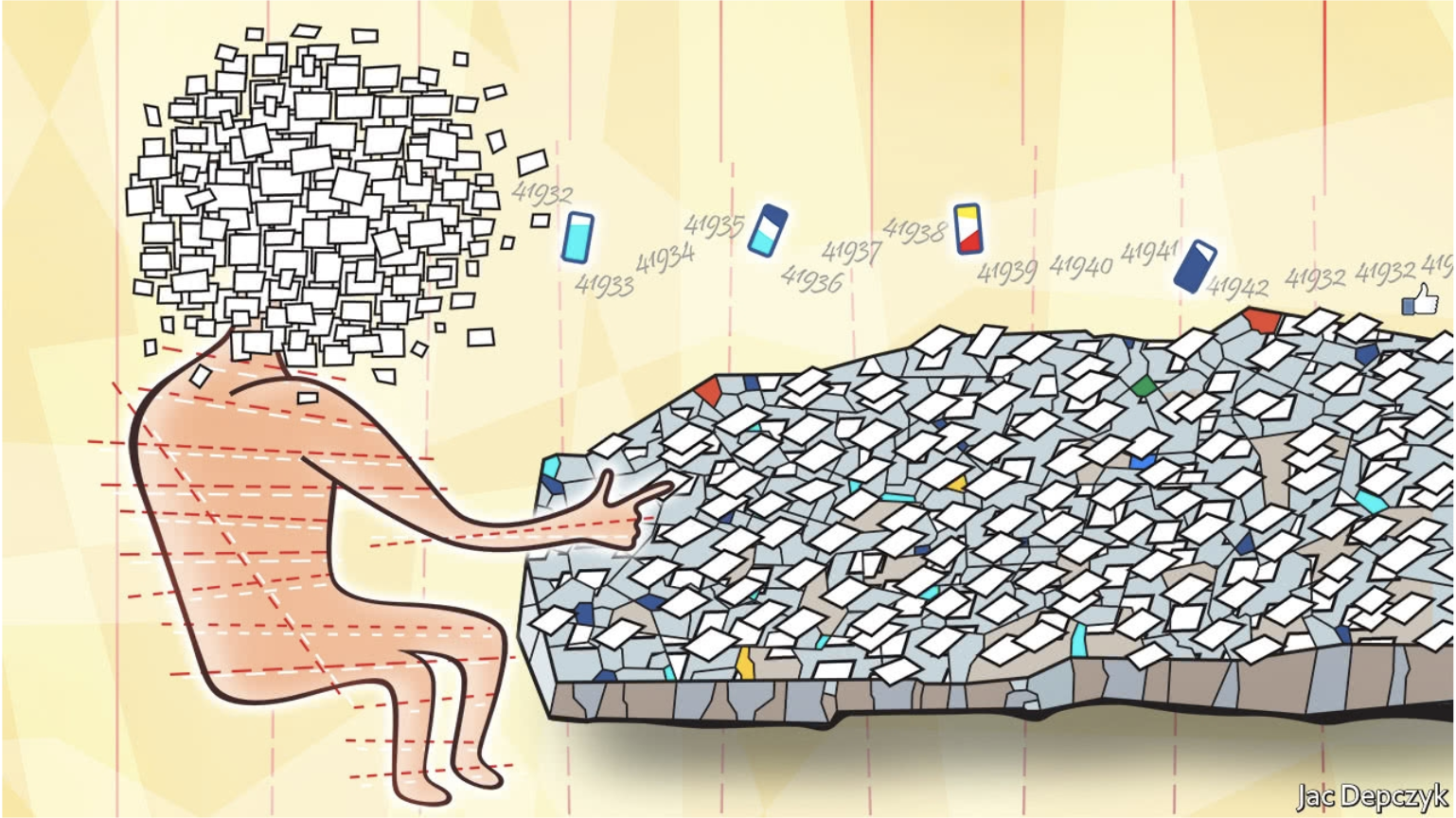

FOR many it is a reflex as unconscious as breathing. Hit a stumbling-block during an important task (like, say, writing a column)? The hand reaches for the phone and opens the social network of choice. A blur of time passes, and half an hour or more of what ought to have been productive effort is gone. A feeling of regret is quickly displaced by the urge to see what has happened on Twitter in the past 15 seconds. Some time after the deadline, the editor asks when exactly to expect the promised copy. Distraction is a constant these days; supplying it is the business model of some of the world’s most powerful firms. As economists search for explanations for sagging productivity, some are asking whether the inability to focus for longer than a minute is to blame.

The technological onslaught has been a long time building. Bosses no doubt found the knock of the telegraph boy or the clack of the ticker-tape machine an abominable interruption. Fixed-line desk phones were an intrusion in their day, before the mobile phone brought work interruptions into the home. But the web is different, with its unending news cycle, social networks humming with constant conversation, and news feeds algorithmically structured to keep users scrolling and sharing. The louder the din, the greater the distraction—and the harder to tune it out for fear of missing important information.

Distractions clearly affect performance on the job. In a recent essay, Dan Nixon of the Bank of England pointed to a mass of compelling evidence that they could also be eating into productivity growth. Depending on the study you pick, smartphone-users touch their device somewhere between twice a minute to once every seven minutes. Conducting tasks while receiving e-mails and phone calls reduces a worker’s IQ by about ten points relative to working in uninterrupted quiet. That is equivalent to losing a night’s sleep, and twice as debilitating as using marijuana. By one estimate, it takes nearly half an hour to recover focus fully for the task at hand after an interruption. What’s more, Mr Nixon notes, constant interruptions accustom workers to distraction, teaching them, in effect, to lose focus and seek diversions.

Could this explain the rich world’s productivity slowdown? In a paper published in 2007, Sinan Aral and Erik Brynjolfsson, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Marshall Van Alstyne, of Boston University, analysed firms’ use of information technology and its effects on labour productivity and revenue growth. They found an inverted U-shape pattern associated with multitasking and productivity. An initial increase in multitasking from the increased use of IT seems to raise productivity. But later, the accumulation of balls to be juggled reduces performance and increases the incidence of error.

It does help workers in all sorts of ways. It speeds communication and allows documents to be shared remotely. The web makes finding information far simpler and quicker than it was in a world of paper archives. Productivity surged in the late 1990s and early 2000s as e-mail, digital databases and the web spread. The benefits technology brought, at that time, seemed to outweigh the cost of distraction. Since the mid-2000s, however, productivity growth has tumbled, perhaps because the burden of distraction has crossed some critical threshold.

But this is surely not the whole story. Performance across industries does not fit very well with the idea that distraction is the main cause of weak productivity. Over the past decade, labour-productivity growth in both manufacturing and construction has been particularly disappointing—and the problem can hardly be desk jockeys frittering away time on Pinterest.

Weak productivity is also a consequence of the reallocation of workers from industries with relatively high rates of growth to more stagnant ones. In America health care and education, where labour productivity is persistently low, account for more than half of total employment growth since 2000.

How then to reconcile evidence of the toll taken by new technologies with the difficulty in detecting a productivity cost? One possibility is that firms have not been as strenuous as might be expected in maximising output per worker. Employment does not fall much in response to minimum-wage rises because output per worker goes up. That is partly because workers try harder and partly because firms, faced with a new cost, focus more on tracking worker performance. Similarly, productivity leapt in the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis, and not because firms laid off less productive workers. Rather, workers appear to have upped their game to convince bosses not to sack them. After a decade of low wages and high profits, firms may be feeling complacent. That, and their consequent failure to invest, may be a better explanation of weak productivity than workers’ distraction.

Tweet dreams are made of this

Whether or not brains fried by constant interruption are slowing growth, the digital deluge takes a toll. Mr Nixon reckons that distracted workers become less empathetic, a serious side-effect in an economy where human connections with customers are cast as a defence against automation. Distraction also appears to reduce reported happiness, and that effect may be magnified if it means that fewer tasks are completed to the workers’ satisfaction—or if the source of the distraction is another distressing news alert. So this is yet another reason to yearn for a truly tight labour market: when firms cannot spare an idle moment they might get serious about trimming productivity-sapping intrusions from the workplace, to everyone’s benefit. Right, time for a tweet.

This article is sponsored content from The Economist. To enjoy more of the same, subscribe to The Economist, 12 weeks for £12.